Virginia Woolf’s Freshwater

By Ian Butcher

It is a little-known fact that Virginia Woolf, known principally for her ground-breaking novels and essays about art and literature, also wrote one play, which was designed to be acted by her family and Bloomsbury Group friends. The play, Freshwater: A Comedy, underwent two iterations in 1923 and 1935, and ‘starred’ the legendary actress Ellen Terry. Although light-hearted, the play deals with a number of subjects dear to Woolf’s heart, including the entrapment of women in restrictive, male-determined roles.

Virginia Woolf

Adeline Virginia Stephen was born on January 25, 1882. Like many middle-class girls of the age, she was educated at home by her affluent parents while her brothers were sent to school, a gender disparity she resented, and which features as a theme in much of her writing. As children, Virginia and her siblings regularly wrote plays and performed for the family and servants. One such was the tragedy of Clementina’s Lovers, written by Thoby Stephen, Virginia’s brother.

Virginia’s first novel was The Voyage Out in 1915, followed by Night and Day in 1919. Her distinctive style was found in Jacob’s Room of 1922, followed by works which would be considered her iconic masterpieces: Mrs Dalloway (1925), To The Lighthouse (1927), and The Waves (1931). There were also semi-political works such as A Room of One’s Own (1929), Three Guineas (1938), and the pseudo-biographical novel Orlando (1928). Her legacy in these modernist novels was her unique use of narrative devices, notably the ‘stream of consciousness’ style including interior monologue.

She wrote essays on literary and artistic theory, literary history, women’s writing, feminism, and the politics of power. In 1918, she was writing nearly a review a week for The Times Literary Supplement. She was a prodigious letter-writer and keeper of diaries: she left behind some six volumes of letters and six volumes of diaries. In 1917, Virginia and her husband bought the Hogarth Press. Type-setting and working the presses themselves at the beginning, they were responsible for publishing major works, such as T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land in 1922, E. M. Forster, and the couple’s own work. Initially, Virginia’s sister, Vanessa, designed Virginia’s book dust jackets. The Woolf partnership proved a powerful force both in their personal lives and subsequent artistic developments.

Throughout her life Virginia suffered from severe depression and psychotic episodes. Her husband, whom she married in 1912, felt that her fragile health meant that she would not be capable of looking after a child and they remained childless, another theme in her work. Virginia attempted suicide in September 1913, and on 28 March,1941, after another period of deep depression, she filled her pockets with stones and drowned herself in the River Ouse.

The Bloomsbury Group

The Bloomsbury Group was an informal group of like-minded friends brought together by a common interest in literature, art, philosophy, and social and political theory. Members of the circle were some of the most important writers, artists and philosophers, critics and intellectuals of the twentieth century. Members included Roger Fry (artist), Duncan Grant (painter), Lytton Strachey (biographical writing), E. M. Forster (novelist) and John Maynard Keynes (economist working for the Treasury). Virginia Woolf and her husband, Leonard Woolf, were central members, as was Vanessa Bell (Virginia’s sister and artist) and her husband Clive Bell. Other peripheral personalities fluidly gravitated around the group, including T.S. Eliot and Bertrand Russell (philosopher), Lady Ottoline Morrell (society hostess), Vita Sackville-West (writer) and Harold Nicolson (diplomat). This was supplemented by the passage of lovers, admirers, friends and various artists and poets.

The group, sometimes referred to as the ‘Bloomsberries’ (Dent), had no manifesto nor any official list of members. It originated at Cambridge University where Virginia’s brother, Thoby Stephen, was a student. In 1902, some of the male members were asked to join the Apostles, an intellectual group where once a week a member would give a talk which the others would debate. These men formed what was to become the core of the group. This focus on lively debate would be a central dynamic of the Bloomsbury Group, which really started around 1904, meeting on Thursday evenings in the then unfashionable part of London. The sisters – Virginia and Vanessa Stephen – hosted these meetings as ‘at homes’. No topics were off-limits, and sex and sexuality were often discussed. The group championed sexual freedom and equality, and there was much swapping of partners, both heterosexual and homosexual. Members were subject to intense scrutiny from the others. The truly sensational aspect of this group of friends is the diverse and significant body of work they left behind in many disciplines which would profoundly influence twentieth century intellectual and artistic life. As Dorothy Parker famously wrote “they were living in squares, painting in circles and loving in triangles” (Kelly). The group was not always universally liked, especially in the post-war period, was seen as elitist and self-regarding with their effete credo of ‘art for art’s sake’ (Forster).

Freshwater

Nell: “It makes me think such dreadful thoughts. I don’t think I could really dare tell you. You see, it makes me think of – beef steaks; beer; standing under an umbrella in the rain; waiting to go into a theatre; crowds of people; hot chestnuts; omnibuses – all the things I’ve always dreamt about. And then, Signor snores. And I get up to go to the casement. And the moon’s shining. And the bees on the thorn. And the dews on the lawn. And the nightingales forlorn” (Woolf 1976 28-29).

Apart from the evenings of serious discussions, the Bloomsbury set also knew how to enjoy itself. Initially using plays for play-reading evenings, this developed into frequently held theatrical evenings which consisted of treasure hunts, fancy-dress parties, Shakespeare and the Classics, can-can dancing, ballet, music-hall songs, plays and skits that could be, in Virginia’s words “sublimely obscene” (Woolf 1976 p.v). Though they were primarily entertainment, there was frequently an undercurrent of didacticism: revealing secrets, resolving disputes, satirising embarrassing habits, and flattering guests. Previous productions had included Milton’s Comus; a comic drama in rhyming couplets called The Last Days of Old Pompeii ; a shadow play about John the Baptist featuring a severed head made out of cardboard and covered in red gelatin; and Don’t Be Frightened or Pippington Park (about a wealthy man who had molested a young woman in the park). This latter included the eminent economist, Maynard Keynes and his ballet-dancer wife, Lydia Lopokova, doing a pas de deux (Miscellany).

Although these performances often took place in Bloomsbury, the group regularly congregated at their various homes outside the capital. Virginia and Leonard lived at Monk’s House near Rodmell in East Sussex: Vita Sackville-West (Virginia’s lover) lived at Knole, and also Sissinghurst Castle Garden in Kent: Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell lived nearby at Charleston Farm, and Maynard Keynes lived at Tilton House with his wife. Other houses belonging to more peripheral members were also visited. All these venues were used for Bloomsbury theatrical evenings

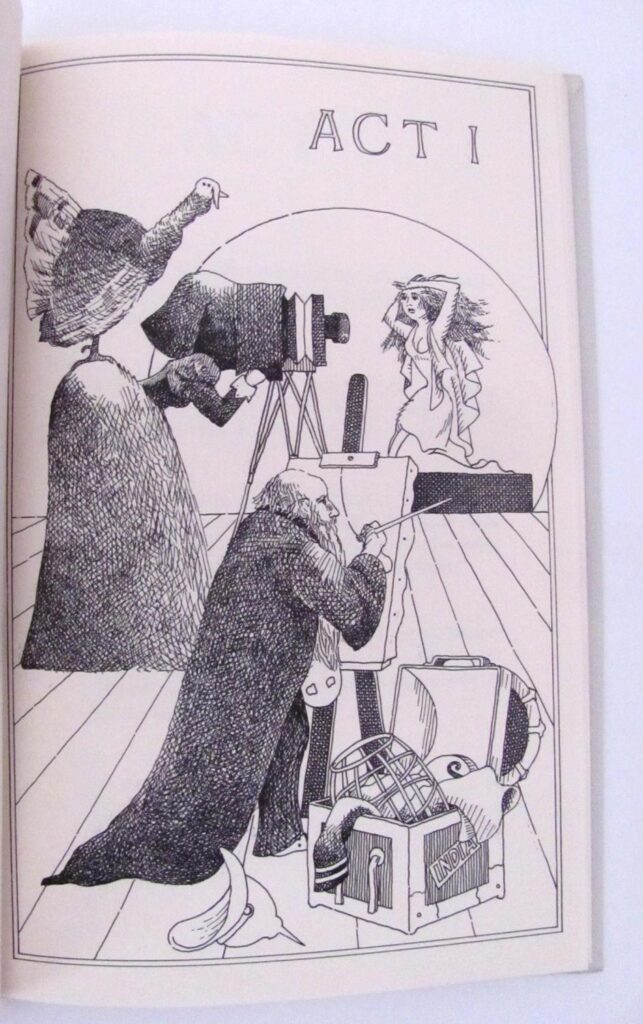

Although Virginia wrote a number of articles about the theatre and its famous actresses, it comes as a surprise to learn that Virginia wrote a play. It was her only play, and only produced once in her lifetime. She had had the idea in her mind for a long time, since 1919, mentioning a play about her relations, Julia Margaret Cameron and Charles Hay Cameron. It was especially for one of these evenings that Virginia wrote Freshwater: A Comedy. There are two manuscripts which were discovered in 1969 by Olivier Bell, a few weeks after Leonard Woolf’s death. Virginia started the first draft in 1923 and put the script in a drawer. Twelve years later in 1935, she revisited and totally rewrote the play which was put on in Vanessa Bell’s London studio at 8 Fitzroy Street on January 19, 1935. Virginia directed it herself.

Vanessa’s studio was L-shaped with a curtained stage. The play was performed in an atmosphere of levity and noise from the high-spirited audience of around eighty guests who were in party mood. The dim stage-lighting made it difficult to hear and see what was happening. After the hour-long, three-act show, the guests adjourned down a hallway to Duncan Grant’s adjoining studio for a party. Virginia declared in her diary the following day that it was an “unbuttoned laughing evening” (Woolf 1976 p.vi).

Although Virginia described the play later as “tosh” or frivolous, there are indications that she took the matter very seriously. She disappointed a number of friends when she abandoned the 1923 version, writing “I could write something much better if I gave up a little more time to it: and I foresee that the whole affair will be much more of an undertaking than I thought” (Woolf 1976 p.viii). She also wrote in her diary, in a nod to Shakespeare’s Bottom in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, that that she planned to “hire a donkey’s head to take [her curtain] call – by way of saying This is a donkey’s work” (Farfan p.3). This, and the fact that the play was heavily rehearsed over the preceding summer, and that Virginia had researched in some depth about her great aunt, Julia Margaret Cameron, attested to her focused intent not to take it lightly. Writing Freshwater was comic relief for Virginia while she was writing Mrs Dalloway.

The title Freshwater is named after Freshwater, Isle of Wight, where Julia Margaret Cameron lived in her home, Dimbola Lodge, surrounded by fellow artists and literary figures. The play takes place on some rocks called The Needles off the Isle of Wight. The plot initially revolves around the Camerons preparing to leave for India, when their coffins arrive, however the main focus is the attempts by the young actress – Ellen Terry (Nell) – to escape her stifling marriage to the much older painter, G.F. Watts. She meets the handsome, twenty-two-year-old Royal Navy lieutenant, John Craig. They fall in love, and he offers to take her back to Bloomsbury. She throws her wedding ring into the mouth of a passing porpoise and elopes with Craig to pursue a life of creative freedom as an actress. Craig is the only ‘made-up’ character in the play, perhaps not a learned figure but someone to give freedom and love to Ellen.

The Dramatis Personae of the 1935 play comprised:

- Mrs Cameron Vanessa Bell

- Mr Cameron Leonard Woolf

- Alfred Tennyson Julian Bell

- Ellen Terry Angelica Bell

- G.F. Watts Duncan Grant

- John Craig Ann Stephen

- Mary and a visitor Eve Younger

- The Porpoise Judith Stephen

- The Marmoset Mitz

Although the play was intended to be comic, there are some themes running through it which have serious intent. Watts is an elderly painter (who painted a famous portrait of Virginia’s father) who makes his young wife Ellen assume rigid poses for hours as ‘Modesty’ without moving and wearing turkey wings. She is the Victorian idea of womanhood, her sterile constraint signifying the outdated attitude of men and the subservient position of women to which Virginia wished to object. When it is briefly believed that Ellen is dead, Tennyson immediately and insensitively seizes the opportunity to write an “immortal poem” as “there is something highly pleasing about the death of a young woman in the pride of life” (p.40). He is crestfallen to learn that she is not dead, and he will not be able to continue his poem.

The action springs from some true facts. The real Ellen Terry, after her separation from Watts, ran off with Edward Godwin; she and Godwin had two children who adopted the surname Craig, after seeing the Scottish island Ailsa Craig on a family holiday. The real Terry did pose for Watts, though she was not the subject of an ode by Tennyson. Ellen says in the play “Nobody ever jumped over your head and dropped a white rose into your hand and galloped away?…I was walking in a lane the other day picking primroses when –“ The story goes that the playwright, Charles Reade, was out foxhunting, leapt over a hedgerow, recognised Terry and made her a financial offer to lure her back in theatre. The otherwise absurdity of the inclusion of the porpoise may be partially explained by Vanessa bell’s nickname of ‘Dolphin’, because of her “undulating movements” (Farfan p.11). The strange marmoset monkey which is a character in the play was in real life a real “sickly pathetic” marmoset, Mitz, that Leonard Woolf nursed back to health and became a fixture of the Bloomsbury household (Nunez).

The play is replete with cultural references, in-jokes and quotes from poetry that only an audience of intellectuals and poets might understand. Tennyson, the Poet Laureate, ludicrously reads passages from his poem Maud and other works throughout, refers to the song Hearts of Oak, and recites snippets from Wordsworth and Matthew Arnold. Nell blabs and misquotes poetry, without appearing to understand what she is saying:

Beauty is truth: truth beauty: that is all we know and all we ought to ask [John Keats Ode on a Grecian Urn, “Beauty is truth, truth beauty, – that is all/Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know”]. Be good, sweet maid, and let who will be clever [Charles Kingsley, A Farewell, “Be good, sweet maid, and let who can be clever”]. Oh, and the utmost for the highest, I was forgetting that [Oswald Chambers’ book My Utmost for His Highest] (Woolf 1976 p.28).

Nell continues with “and the nightingales forlorn” [Keats Ode to a Nightingale] and “Are there any apple trees there/” [probably a reference to Christina Rossetti’s An Apple Gathering, “I found no apples there”] (p.29).

Virginia was very interested in the profession of acting, and wrote essays and reviews on the French actresses Sarah Bernhardt and Rachel Felix. She also wrote in admiration about Ellen Terry, Nell/Ellen, the central character in Freshwater. Woolf saw acting as an opportunity for self-expression and liberty, and in a review of Sarah Bernhardt’s memoirs, states that she expects “actresses to lead fuller, richer, more interesting and complicated lives” (Farfan p.4). Acting liberates women from the typical male-determined gender roles which entrap them. Terry’s return to the theatre after her six-year hiatus with her lover in the country, was clearly the source of Virginia’s inspiration for the play. Terry died in 1928, probably one of the most celebrated actresses of her generation.

The day after Freshwater was performed, Virginia wrote that she had an idea for another play, Summer Night. It never came to anything, but, later, in her novel Between the Acts, the character Miss La Trobe directs a musical theatrical pageant of pre-war villagers acting out scenes from English history and literature on a summer night. In Between the Acts was published shortly after Virginia’s death in 1941.

Modern Productions of Freshwater

Freshwater was only produced once in Virginia’s lifetime. However, a number of companies have subsequently taken it up. The play was translated into several languages: Spanish (1980), French (1982), and German (2017). A French production was put on at the Pompidou Centre in Paris in 1982, and in Mainz, Germany in 1994. A production was put on in French in New York in 1983 with an all-star French cast, including Eugene Ionesco, Alain Robbe-Grillet, Nathalie Sarrault – all famous writers. Also Joyce Mansour, a surrealist poet, Guy Dumur, drama critic for Le Nouvel Observateur, and Florence Delay, a writer and professor of literature at the University of Paris. As Nigel Nicolson a descendant and chronicler of Bloomsbury commented, “They couldn’t act, but they acted; they couldn’t sing, but they sang; they couldn’t dance, but they danced” (Hoffman).

In 1989 there was a rehearsed reading of the play in Melbourne, Australia, by the Performing Arts Project at the Linden Gallery. In 2009 in New York, the 1923 and 1935 versions were combined in an off-Broadway production to celebrate Virginia’s 128th birthday. In London in 2012, the play was performed in Virginia’s former home in Gordon Square; a version was also performed at the Woolf home, Monk’s House in Rodmell, Sussex.

Conclusion

Freshwater: A Comedy was Virginia Woolf’s only produced play in a life otherwise devoted to novels, reviews and essays. A unique foray into playwriting by a major literary figure. It was her contribution to the regular theatre evenings enjoyed by her coterie of friends. Although she considered it to be a light-hearted joke to amuse her family and Bloomsbury friends, little more than an extended sketch, she went to considerable efforts and two drafts to make sure that it was as good as she could make it in terms of research and rehearsals. It is full of literary references, snatches of poetry, and send-ups of current personalities and manners. But beneath the surface some serious matters are being raised, namely the parlous status of women in her society, stifled by the old-fashioned attitudes of men.

Works Cited

Dent, Catherine. 2023. “What was the Bloomsbury Group?”, The Collector, February 23.

Farfan, Penny. 1998. “Freshwater Revisited: Virginia Woolf on Ellen Terry and the Art of Acting”, Woolf Studies Annual, Vol.4, pp.3-17. New York: Pace University Press

Forster, E. M. 2025. “The Concept of Art and Modern Society’s Perception in Art for Art’s Sake”, http://www.kibin.com/essay-examples/the-concept-of-art-and-modern-society’s-perception-of-art-in-art-for-arts-sake-an-article-by-em-forster-Nof5ESA1/

Hoffman, Eva. 1983. “Rare Cast from France in a Rare Woolf Play”, New York Times, Oct.22, Section 1, p.9.

Kelly, Thomas. “The Bloomsbury Set of Mecklenburgh Square”, https://goodenough.ac.uk>the-bloomsbury-set-of-mecklenburgh-square/

Nunez, Sigrid. 2019. The Marmoset of Bloomsbury. New York: Basic Civitas Books.

Virginia Woolf Miscellany. 2003. “Editor’s Preface, Freshwater: A Comedy – Monk’s House,1975. http://virginiawoolfmiscellany.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/vwm63summer2003.pdf/

Woolf, Virginia. 1976. Freshwater: A Comedy, ed. Lucio P. Ruotolo. New York: Harcourt Inc.

Ian Butcher is an independent scholar with degrees from the University of Kent, the University of York, and The Open University in the UK. He was a lecteur d’anglais at the University of Nice, France. He has published a number of academic articles on T.S. Eliot, Annie Ernaux, Samuel Beckett, Harold Pinter, and on Titology and working titles of literary works. He lives in Belgium and Denmark with his Danish wife, Marianne.