On belonging and being here to stay

By Helene Grøn

From the moment she emerges from behind a screen, Hanin Georgis wants you to know she is nothing like the Arabic woman portrayed in media and politics. She demands to be understood on her own terms in a performance that highlights this as a structural, aesthetic and political challenge.

The dramaturgical language of Den Anden Arabiske Kvinde underscores the demand to navigate identity against rigid categorisations of Arabicness, but equally so within narrow definitions of Danishness. Throughout shifting sequences – anecdotal to historical – the question of belonging remains a constant: who can understand themselves as Danish? Who has something viable and treasured to bring to society? Whose contributions and cultures evolve the cultures we share?

The theatrical labour of navigating identity

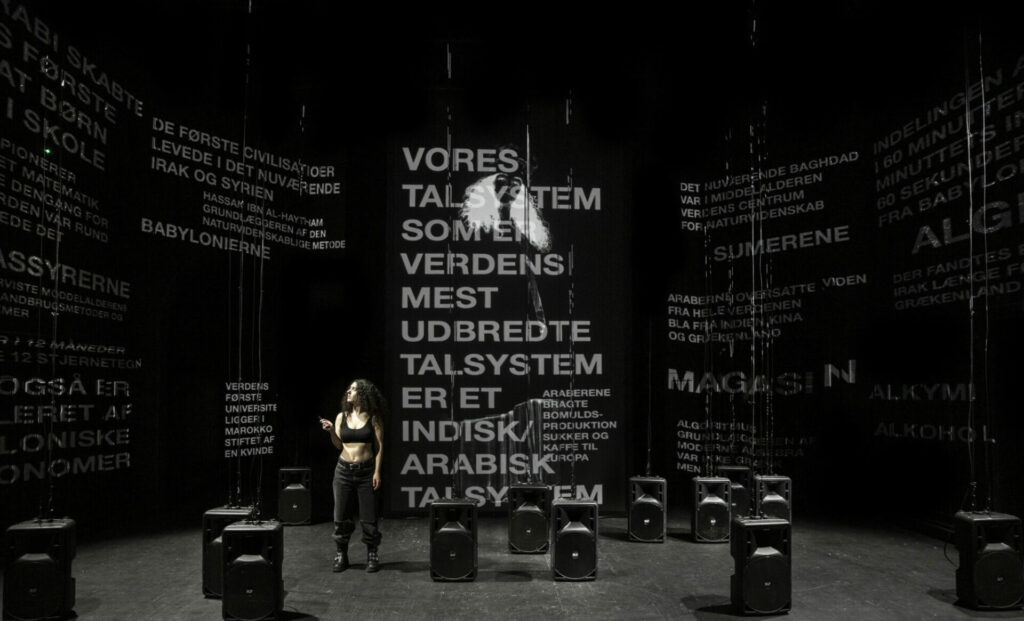

At show-start, the stage is bare and Georgis is dimly lit as she stands, unclothed, stating exactly who the other Arabic woman is: she is not a practicing Muslim, she does not wear a hijab, she loves sex, she drinks alcohol, eats pork and has no time for the kind of stereotyping and exoticism that casts her in a specific role. As she talks, large speakers descend gradually from the ceiling, interrupting her with a steady flow of questions and statements that illustrate the kind of perceptions Georgis has had to work against her whole life: does she eat pork? Does she drink? Are the men in her family oppressive? Where is she really from? But originally from?

She persists, she talks over, she starts again, even as she is interrupted, even as her gestures and speech become more slouched and insecure, showing exactly the kind of bodily, emotional and continual labour of navigating identity and sense of belonging placed on the individual when sharing national and relational space.

The speakers help underscore the shifting mood of the piece; as they turn into props for parties, Georgis shares anecdotes of drinking too much just to avoid confirming stereotypes, or being called ‘my Arabic princess’ by Kaffe-Lars; a Vesterbro-resident she is dating. It is the dark hairs on her arm that causes Kaffe-Lars to call her ‘international’, showing the narrow definition of Danishness that Georgis works against in the first place.

Georgis shares how she has shaved, bleached and laser-removed hair all over her body to accommodate western cosmetic ideals. This section takes the rhetorical shape of an apology to her body, which was, as she reminds us, always beautiful. Georgis gradually gets dressed through the piece, making her body a continual visual reminder of the narrowness of looking Danish, but also of the persistence of Western beauty standards.

Mastering shifts and languages

Georgis’ language throughout the piece masters the shifts between tenderness and a humour that never abandons its kinship with serious contemplation, encouraging the audience to engage with the anecdotes. This is shown, perhaps most clearly, in a sequence where she shares that she is expected to be thankful at every turn, for example when people compliment her language abilities. For several minutes, she tells us “thank you, thanks so much” in different ways as she crouches, making herself smaller and smaller, until she is behind the screen.

There are many striking elements to Georgis’ performance and Özlem Saglanmak’s direction, but perhaps the most notable is the shifting stage-language that allows for these autobiographical instances to emerge alongside historical, narrative material.

With the speakers on the floor, blasting energetic bass-tunes, the light dims as Georgis turns educator. She tells us about Danish words that owe their existence to Arabic ones. She tells us about different women from the Arab world that are already, and have always been, the Other Arabic woman. The screen shows black-and-white animations of these women, stood in empowering positions and adorned clothing, staring directly and uncompromisingly from their historical position at the audience, demanding, much like Georgis, to be seen, heard, understood on their own terms.

From Enheduana, the 4300 year old first ever author, who wrote hymns for the Sumerian gods and goddesses, to Scheherazade, the storyteller in One Thousand and One Nights, who sacrificed herself in marrying the monarch Shahryar, who had been marrying and beheading a noble-birthed virgin every day ever since finding out his first wife was unfaithful to him.

Georgis asks why these women have been absent from her, and our education, thereby suggesting that the interludes have a double-task: including these stories in education or the cultural landscape more broadly would have given an individual as well as societal frame of reference for understanding and historicising the other Arabic woman, yet this is exactly what Georgis is doing by putting them in her show. At one and the same time, the sequences position her as a teacher as well as in the lineage of these women.

Expanding Danishness

Questions of cultural belonging are also explored through stories around food. Georgis sits on the floor as a child, packed lunchin hand. A boy in her class taunts her that her dolmades look like poo, and she becomes immediately ashamed. Later in life, she sees restaurants and shops alike taking to Middle Eastern food with hummus and tahin being more and more available. Her friends now give her advice on how to make the things she used to eat as a child, the dishes that were then considered abnormal to bring into the cosmos of the schoolyard. She marvels at how people pronounce the words and dishes she is so accustomed to, suggesting that what has been lacking is not this culinary and cultural knowledge, but rather opportunity for and understanding of exchange.

The most disarming story around food is perhaps when Georgis tells of preparing dinner with friends, who suddenly realise she has a story of flight and forced migration. As they are cooking together, she shares both their questions and her inner dialogue; she shows the discord between what they ask of her and what she can share, thereby foregrounding the implicit demand on a person to tell a story.

With a direct eye for how many Danes conversationally dismiss staying with difficult topics, she states that if she tells this story, at some point someone will change the subject, but, as she reminds us, she is the constant carrier and owner of this story that is not just a story, but a whole, branching life. These micro-relational moments show exactly how relational moments hold the possibility for expansion and exchange.

The other Arabic woman is here to stay

With Den Anden Arabiske Kvinde, Georgis makes visible the constant labour and love involved in belonging, in making a life, and in making the kind of cultural work that pushes critical dialogues: The show intersects with debates around who can be Danish that have sometimes taken shape exactly around race and ethnicity, and that Georgis, as many others, has also had to contend with in castings and as a performer. Apart from reaching a theatrical stature in and of itself, Georgis’ show also expands creative possibilities for the sector more widely. As she states at the end of the show in something like a triumph, to an audience that will soon give her a standing ovation: den anden arabiske kvinde is here to stay.

Den Anden Arabiske Kvinde spillede på Blaagaard Teater fra d. 20. januar til d. 11. februar 2023 og igen fra. d. 23. maj til d. 31. maj 2023

Læs mere her

Medvirkende: Hanin Georgis

Idé & manuskript: Hanin Georgis

Instruktion: Özlem Saglanmak

Scenografi & kostume: Mai Katsume

Lysdesign: Mathilde Niemann Hyttel

Lyddesign: Nanna-Karina Schleimann

Koreografisk konsulent: Ida Frost

Videodesign: Mai Katsume & Mathilde Hyttel

Manuskriptkonsulent: Anna Skov

Instruktørassistent: Hildur Ýr Jónsdottir

Forestillingsleder: Merethe Bahn Trolle

Instruktørkonsulent: Sargun Oshana

Helene Grøn is a writer of plays and prose, and a postdoc at the University of Copenhagen