Celeste by Amelia Høy at Mungo Park

By Helene Grøn and Anika Marschall

Celeste is Black US-Danish writer and director Amelia Høy’s debut and part of Mungo Park’s new sketch format. Her dramaturgy is driven by the potential violence looming large in what is hinted, but never stated, to be the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests. With longer, deeper and more familial roots than the recent protests, Høy’s story takes place not in the streets or in the heart of the action, but in the character Thomas’ living room during his 60th birthday. As he receives calls from his absent friends and daughter Celeste, Thomas unfolds the events of his life and the realities of living as a biracial family in a mostly white, Danish country. Høy tucks at the edges of Thomas’ understanding that his life might be different from that of his Black daughter, catalysed, it seems, not by the self-reflection of critical awareness, but rather the phone calls he receives from the police inquiring as to the whereabouts of Celeste after there has been an assault at a protest she was at.

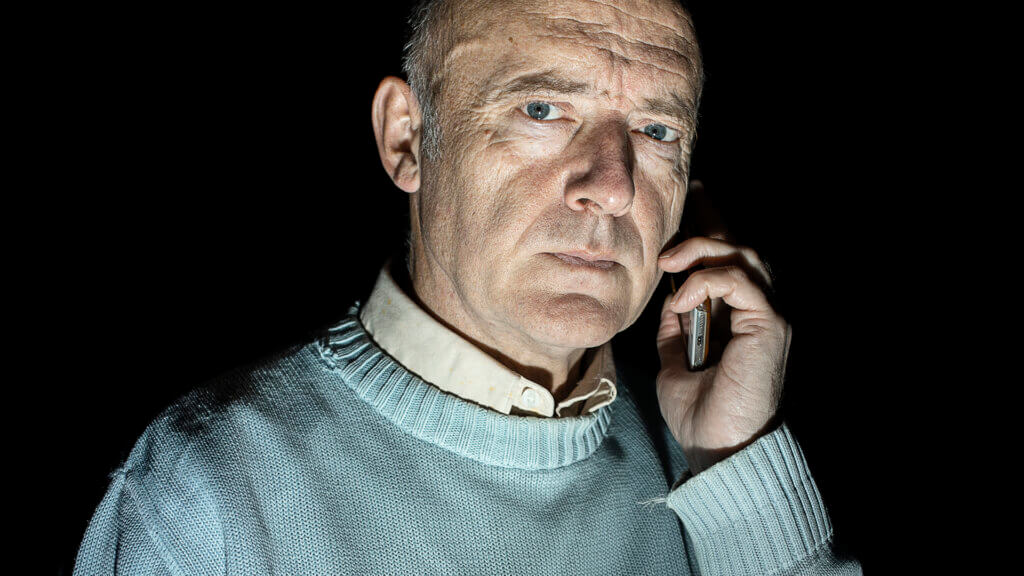

Detailing the history of violence in his family, from his alcoholic brother and Celeste’s anger at being treated unequally, to Thomas himself losing his temper with one of Celeste’s teachers, Thomas’ reflections seem mostly to be uttered from the confines of a midlife crisis and the grief of losing his wife before his time. As Henrik Pip, portraying Thomas, took the stage alone in front of a mostly white audience, we wondered whether Høy’s choice to stage Thomas’ rather than Celeste’s story is not simply a conversation starter about racism, but a strategic choice, which gestures towards the anti-racist work that is yet to be done.

The happiest country

The stage space in Celeste is undoubtedly a Scandinavian living room set for a birthday celebration: the grey, tasteful and not quite comfortable sofa, the splash of colour of the rug and the table set with a Danish flag, a cake with a candle and a pot of coffee. As the stage lights go up, we see Thomas wearing a triangular red party-hat along with his otherwise sober outfit. We get the sense that this is exactly the amount of silliness and celebration that would be accepted in this sphere, but as he is by himself, the hat seems to instead make a spectacle of his loneliness. It is within this setting that Thomas acknowledges the audience and begins addressing it with a slow-paced monologue, which ranges from reflections about his biracial family life, Celeste’s upbringing after the death of his wife, and his own reckonings with what he thought his life would be.

During much of the play, the stage-space remains intensely dark, punctuated only by a few sources of light: the candle on the cake, the dim lamp by the edge of the sofa and a neon pipe light upstage left. It seems as if we audiences are not just offered a glimpse into his spatial privateness, but the set and lighting design throws shade in a way that could be symbolic for his innermost workings. One of the more notable times Høy uses this stage space, is when Thomas indulges in expectation versus reality. He walks around the stage, sipping teaspoons of coffee topped with whipped cream, always facing the audience as he lays out all the things that were supposed to happen: he was supposed to marry someone, grow old with them in a graceful way, and then die quietly in his sleep next to this person. He was supposed to be a ‘superfar, superman’, someone who could handle everything. He was supposed to read books, to holiday in Italy, speak Italian fluently and to pick up knowledge about wine. Sounding increasingly desperate about his high hopes, he retreats to the darkest corners of the stage, and we get the sense the lighting is used to denote the horror looming large at the edges of the unrealistic Scandinavian dream of living a middle class life in one of the happiest countries on earth.

Fighting for Equality

At the heart of Høy’s play is the question of what happened to the eponymous but absent character: Celeste. The question is imbued with the potential of violence, and it rises with increasing urgency as the play progresses. All we hear of Celeste’s own voice are a well-formulated email distancing herself from her father during a gap year and the ephemeral backstage voice-work of Høy as she reacts with different enunciations of the word ‘far’ to Thomas’ monologue. However, even then, she is filtered through Thomas’ reaction to her email or Thomas’ own imagination of his daughter’s voice in his head. Audience members might be unsettled by the fact that we never hear Celeste’s own version of events, however, herein lies perhaps the brilliance of Høy’s dramaturgical choice. We are left sitting with these questions of her identity as we piece together who she might be from the most disparate sources: her father’s words, a monotonous yet suspicious police officer calling Thomas to inquire about his daughter’s whereabouts, and from a social media broadcast Thomas follows, telling the events of the assault at the demonstration. Together, these elements of Celeste’s story told by her father, the media and the police make visible the systemic structures of violence Celeste finds herself in, which in turn makes the audience question how comfortably we sit within these structures, too.

At one point in the monologue, Thomas questions his own part in this, as someone who perhaps encouraged his daughter to fight back out of fear that she would become the victim. Here, Celeste’s ephemeral vocal intervention, with a gentle but mocking sounding ‘far’ from backstage hints at another version of events, which the audience is never exempt from navigating. This is most pertinent in the broadcast Thomas follows; we learn that two men were assaulted at the protest that Celeste took part in, and that they both have ‘white lives matter’ tattoos. The attacker is first described as a ‘protestor’, then a ‘woman’, and then a ‘non-Danish protestor’. Although we hear Thomas give himself credit throughout the play for being an open-minded individual reflected in his life choices and his ‘superfar, superman’ love for his wife and daughter, he never wakes up to the difficult emotional, cognitive and material labour he has to do to understand his own position in a world shaped and determined by hetero-patriarchal myths. It is exactly here that the main conflict of the performance plays out; without doing this, Høy seems to suggest, Thomas will never be able to escape the angst of his midlife crisis or be able to be there for his daughter.

And Celeste? The terms of conflict seem much larger for her. As the audience are told the story of a life where she has had to stand up for herself throughout, sometimes with pre-emptive strikes towards others who would presumably enact the same or worse punches on her, we are asked where the ethical line of violent means and self-defence is drawn and for what reasons. If the danger for one character is a bruised ego, and for the other it is being made ‘non-Danish’, imprisonment, or even premature death, the terms on which Thomas and Celeste enter the world even if they are within the same family are radically different.

However, Høy also nuances the theme of violence by gesturing to other forms of resistance and fight to survive systemic violence against racialised people by including Thomas’s memories of Celeste’s fierce mother in her role as caretaker and community builder. As a Black mother, she not only took care of Celeste, but also the neighbour’s daughter. In a memory where she combs both their hair in the middle of the street, Thomas says she was trying ‘to give both girls a culture’. When Thomas tells his wife to take care of herself, she says fighting for justice is taking care of ‘us’, while she points to herself. Within these monological outpourings, there is the hint of something that might have sustained Celeste and her childhood friend in another way; a way of resistance that includes love, cultural practices and care for self and others.

The master’s dramaturgical tools

Høy was inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement in Denmark, and wrote and directed Celeste in the hope of making visible different forms and layers of racism in a contemporary white majority Danish society. In that, Celeste centres on whiteness. While the storytelling names racism, it equally focuses on a white majority Danish audience, who can laugh difficult situations off, judge and confuse the daughter’s politics and her stubbornness or confidence in herself, and misunderstand the visibility and invisibility of violence as something that has nothing to do with their lives. Yet, Celeste perhaps offers white majority Danish audiences an opportunity to think of themselves as white in the first place, and realize that racialisations run deep within all our homes and family structures, no matter the race of our children and partners. Therefore, while Celeste might be a starting point for some to engage with race for the first time as theatre audiences, decolonising the theatre and our behaviour and unlearning habitual ways of thinking and telling stories arguably takes a majority effort across different theatres and institutions, as well as an intergenerational, collective fight.

To pinpoint the dramaturgical stakes of Celeste, the words of Audre Lorde, who spent her final years living on Saint Croix, a former Danish colonial island where Queen Mary famously led the violent rebellion of enslaved people against Danish colonial masters in 1878, come to mind . The Black, lesbian, feminist, mother, poet and warrior writes:

“The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us to temporarily beat him at his own game, but they will never allow us to bring about genuine change.”

In Celeste, the master’s tools are limited to dramaturgical devices such as the monologue, the spatial structure of the audience facing the stage head-on and naturalism, to name but a few. This is not to say that the play is not powerful in addressing whiteness and using these devices or tools dramaturgically to intervene in the otherwise canonical range of stories, which focus on questions of racism as an integral part of living in a white majority postcolonial Danish culture told on stage in Denmark. But, Høy’s dramaturgical choices in Celeste also make transparent the burden to educate, share narratives of violence and trauma and hold the powerful accountable, which is more often than not placed on marginalised people. There is more work to do and risks to take in bringing about genuine change and centring our interwoven collective well-being and shared social responsibility for anti-racist struggles – work that goes beyond ushering white audiences into sole introspection through feelings of guilt or sympathy, as so often invoked by theatre plays about racism and their dramaturgies.

We need to recognise the tools for solidarity that are already there and the tools of resistance championed by Black grassroots activism: naming the problem of racism while shifting language and terms of privilege and allyship; presenting a pluriversality of stories and intersectional perspectives, practising compassion and care and ‘listening across difference’; redistributing material and emotional resources; supporting existing infrastructures such as The Union in Copenhagen and tackling different forms of exploitation (including classism, capitalist power and ecological extraction); teaching others and generating knowledge for critical thinking, rather than solely consuming information about racial equity. As the Combahee River Collective and the Black Panthers have championed before, the goal can only be to work towards collective, rather than individual liberation. If there is a place to practice what it might mean to unsettle centres of power, to rewrite histories and reimagine futures, to think, feel and act differently, to sense that the world could also be otherwise and the existence of different cosmologies and taking seriously the tasks of decolonising, it is perhaps the space of performance.

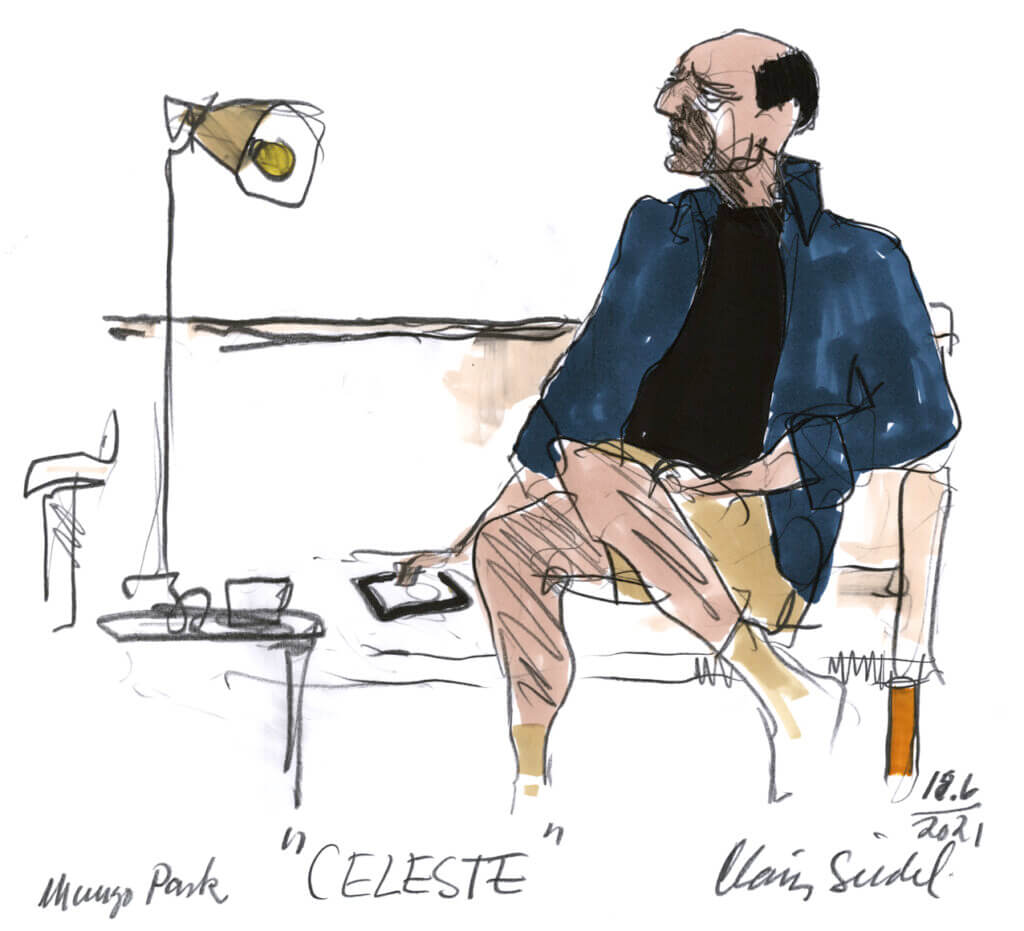

Celeste ran at Mungo Park 18.07-19-07 2021 and will run again from 31.08. to 07.09. 2021.

Instruktør og dramatiker: Amelia Høy

Medvirkende: Henrik Pip

Lyddesign: Emil Bøll

Helene Grøn er Videnskabelig Assistent ved Københavns Universitet, Institut for Engelsk, Germansk og Romansk.

Anika Marschall er Postdoc ved Aarhus Universitet, Institut for Kommunikation og Kultur, Dramaturgi